Mission: End the tuna industry’s war on dolphins.

Everyone agreed it was impossible: convince the world’s largest tuna firm to be dolphin-friendly. And bind them under contract to guarantee it.

Other than the great driftnet kills, the earth’s largest kill of dolphins

has been due to a fiendish methodology employed in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

This reality has been finessed and smoothed tuna industry PR, which has sought to equate the terms “incidental kill” with “accidental kill” in the public mind. So for this story let us first clear that up: the dolphins are intentionally targeted, and that’s why they die.

Here’s how it works. Over the course of co-evolution, a single species of tuna developed a behavioral trick in a special area, and upon that trick hangs the story.

Most tuna don’t have any reason to associate with dolphins. But Yellowfin tuna have learned to swim underneath them in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. It’s out of the dolphins’ control, and led to a terrible calculation by tuna fishermen. The dolphins would be sacrificed.

The Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP) is about a 6 million square mile area roughly off the coast of central america. It’s characterized by a shallow and abrupt thermocline, with warm waters overlying relatively cold waters. Dolphins, which breathe air, spend most of their time at or near the surface.

Yellowfin tuna, which are roughly the same size as dolphins and competitors for food fish, prefer to swim in the cold water below the thermocline, where their thermodynamic efficiency is better. However, swimming down there means it’s harder for them to locate surface prey to eat.

What some yellowfin did was to apply a stationing behavior usually seen only in young fish, to spend their entire lives several hundred feet below herds of dolphins. This worked out so well for them that eventually a large percentage of all the adult yellowfin biomass was stationed beneath dolphins. They’d use the dolphins to find food, and when the dolphins started their sonically-complex feeding, it would alert the yellowfin tuna which would zoom up and go into a feeding frenzy, biting everything they saw.

The dolphins gained no benefit; it was like being followed by dangerous bandits who could travel faster than you. You could never lose them, and they’d steal your food every time you fed. This parasitism became a major ongoing stressor for dolphins in the ETP, but there wasn’t anything they could do about it.

Prior to the late 1950’s dolphins could lead their tuna to human baitboats, in a true symbiosis: the only losers were the tuna.

Or was there? Actually, dolphins would work with humans when given a chance. After WWII, baitboats were deployed to try catching tuna. The boat full of pole-and-line fishermen would chum the water with a few “bait fish”, and try to get a tuna feeding frenzy started.

The dolphins quickly learned that it was a good way to get rid of their tuna parasites, and started using baitboats as “cleaning stations”. When a baitboat was sighted by the dolphins, they would make a beeline for it, and get a few mouthfuls of food. But there wasn’t much actual bait fish on offer – the main benefit to the dolphins was that the far less brainy tuna would hit the unbaited hooks of the fishermen and be pulled into the boat, never to bother them again. The benefit of getting rid of their nemesis was far greater than a snack. But the arrangement suited both humans and dolphins, for the dolphins always brought far more tuna, and they were always yellowfin.

Unfortunately for the dolphins, humans often get fiendish thoughts and act upon them. This particular thought went, “wow, what if we had a giant net and could just catch all the dolphins and tuna, and sort ’em out later on a big deck?”

Thus was born the power-block purse-seine vessel and the fast superseiner, which began displacing baitboats in the late 50’s. The dolphins were no longer partners; they were victims. Tuna generally can’t be sighted from the surface, but dolphins are easy to see. Superseiners would use spotting planes and later helicopters. They would drop small explosives on the dolphins to deafen and slow them down, while the superseiner deployed multiple speedboats to chase the dolphins. The drives of the speedboats also threw bombs; dolphins are acoustic creatures which “see” with sound. The concussion of underwater explosions damages the dolphins’ hearing and disorients their echolocation. They flee, and in the sonic carnage of explosions and speedboat engines, the slower calves fall behind and are lost.

The deafened dolphins would be surrounded by a net 3/4-miles long, which was closed like a purse.

The net would as often as not fold over and drown thousands of dolphins in each set of the net. Millions died this way, as an industry secret.

Finally the exhausted dolphins stop fleeing and form a defensive group, and that’s when the seiner deploys its net. The tuna below the dolphins (if there are any) stay with the dolphins as always. The huge net is gathered together like a drawstring purse; the tuna are caught and the deafened dolphins either drown, escape over the net, or are crushed and discarded. (The tuna industry has long kept alive the fiction that most dolphins survive the process unharmed, but that’s utter BS, not reflected in any real independent monitoring.)

This heinous practice killed off most of the dolphins of key species in the ETP. Roughly 6 million documented deaths in official figures over the years, so maybe double that as a fair real-world estimate. The tuna captains lied then, and lie now. ET’s director of research at Project Delphis, Dr. Ken Norris, was a U.S. tuna-porpoise observer who observed thousands of dolphins dead at a time, and whose life was threatened and log books were thrown overboard. They used the same explosives on him as on the dolphins. Ken testified to this before congress.

So back to our case history; it was a horrible thing but it couldn’t be stopped. The world public got a glimpse of the huge kills in 1975, resulting in marine-mammal protection laws, but once they started being enforced, the U.S. fleet just moved to Mexican ownership and registry, from San Diego to Ensenada, and kept up biz as usual. Well, not entirely usual; they also acquired part ownership by cocaine cartels which found the “front” very useful. (At the canneries, cocaine is euphemistically called “atun blanco”.) And that cheap government-subsidized Pemex fuel was a bonus to the fuel-hungry superseiners, too.

Tuna firms were pressured to stop killing dolphins, but were afraid to capitulate to environmentalists and conservationists. They decided they had to hold the line, a unified front at all costs, and spin the facts as well as they could. Everyone asked “why can’t there be dolphin-safe tuna?” but even by 1990, it hadn’t been done. Something had to be done to end the gridlock.

But it seemed impossible. The tuna firms were dead-set against it, and had the momentum of decades circling the wagons. Any tuna firm that broke with the others would incur significant costs to do so, and had no assurance that the fractionated mix of conservation and pro-wildlife groups which was pressing them would cease pressure even if they did. There was no mechanism for it to work.

The world’s first international standard for dolphin-friendly tuna entered the marketplaced in 1988 and has been there since, an ET program.

So ET created the mechanism. Acquiring the rights to Flipper, the internationally-known dolphin character, it set up the “Flipper Seal of Approval” program as a first-ever licensing mark for an environmentally-less-harmful product. The clear definitions of dolphin safety and lowered bycatch in the Flipper standard could never be changed by law or by outside parties; it was a binding contractual agreement for a firm and all its subsidiaries to be truly dolphin-safe, and to work with ET to police dolphin-killing around the world. The FSA was the mechanism needed, and small firms began to license it.

But a major firm was needed to break the deadlock, and this came down to personal relationships. In 1989, ET’s Don White met on Maui with Jerry Moss (of A&M Records) who was a close friend of Starkist CEO Tony O’Reilly. Jerry loved the Flipper program and agreed to meet with Tony and propose it to him with his endorsement.

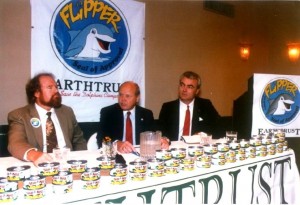

Breakthrough. It had been called “impossible” by every conservation expert: the world’s largest tuna firm contractually agreeing to let ET’s “Flipper” standards guide their global tuna acquisition. ET president Don White and StarKist president Keith Haugy hold a joint NY press conference in the midst of the UN driftnet-ban negotiations.

Jerry’s meeting with Tony broke the deadlock. StarKist, the world’s largest tuna firm, announced they would be dolphin-friendly, and the rest of the world’s tuna firms began to change their tuna acquisition as fast as they could. It was a huge victory, and it only happened due to some real-world wrangling, a credible alternate plan, and the right approach.

“Flipper” became the new face of dolphin-friendly tuna after a bad stumble in the marketplace with the term “dolphin safe” cost StarKist its early benefits.

Analysis: This is a hugely compressed telling of the tale. But it’s a tale worth telling because it’s acknowledged as one of the landmark environmental victories of all time. ET was at its core playing several key roles.And until now, you may not have known that.

In many ways this was the most complex environmental strategy we’ve ever been involved in or heard about. There were a huge number of variables. But we got it done.

Really, who does stuff like this?

Everyone has heard of this victory; it’s universally touted as one of the big environmental wins of the 20th century. Until now, you may have thought it just sort of happened. No, it didn’t. It was a hell of a negotiation over many years.

You may have thought one or more of the “big name” green groups had something to do with it, since they showed up at the StarKist press conference and handed out their PR packets. No. A huge role was played by Earth Island Institute, leveraging Sam LaBudde’s undercover images of tuna seiners and running a boycott which set the scene.

Something not well-appreciated is just how difficult – nearly impossible – it is to get the world’s largest tuna firm to essentially give away its product acquisition decisions to a nonprofit group it has absolutely no control over.

This required ET’s Don White, who deeply cares for dolphins and had spend decades at odds with the tuna industry, to learn enough by immersion to think like a top tuna-firm executive and come up with a business model they could and would sign onto.

Only weeks before the announcement of StarKist licensing the flipper standard, a well-known D.C. foundation director in whom this had been confided stated flatly that it was impossible according to all the major conservation groups, and seemed to wonder what we were smoking.

Oh, and acquiring the global rights to “Flipper” was an interesting task as well, which involved high-level negotiations with the Universal Studios legal department. Those negotiations wound up dropping a major tuna firm as a sponsor of Universal’s Flipper movie since they didn’t meet ET’s dolphin-safety standards, and the film itself ended with ET’s 1-800-FLIPPER number to sign kids up to support the campaign.

And here’s some interesting backstory: Tony O’Reilly was convinced by Jerry Moss to take the dolphin-friendly plunge, but initially decided to use his own logo instead of the FSA. It was a huge mistake which cost his firm millions. Since “dolphin safe” wasn’t a legally-defined term, anybody could say they were dolphin safe, and everybody did. Entirely predictable – and it was predicted in the presentation materials Jerry took to Tony. A chagrinned StarKist had to backpedal and adopt the Flipper standard anyway after losing their lunch money to Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea, and souring their stockholders on O’Reilly’s bold vision.

StarKist stayed with the FSA program for seven years, until 1997 when a smorgasbord of new “dolphin safe” standards and laws started coming out (and Greenpeace started to really backpedal on dolphin conservation). The program did its job, though, pulling together a standard for firms around the world during the crucial years as the world industry went dolphin-friendly.

The FSA now has fewer participants, but it’s the only such program in the market which is inherently immune from free-trade treaties. We’re keeping it ready for another influx of companies if the logo-of-many-definitions “dolphin safe” is overruled by these treaties.